|

| Thomas Benavidez died on June 20, 2010, when a haul truck driver could not see Benavidez's pickup in a blind spot and crushed the smaller vehicle. (Pinal County Sheriff's Office) |

INTRODUCTION

ORACLE, Arizona — Thomas Benavidez never came home that Father’s Day.

His wife and three children knew he had to work, so they didn’t make plans to celebrate that Sunday. Instead, they spent it trying to confirm rumors of his death that swirled through this Arizona community of fewer than 4,000 people and quickly spread alongside details of a mining accident posted to Facebook.

Police photos from the scene show the flipped pickup truck Benavidez had parked in an open-pit copper mine in 2010. A 240-ton truck the size of a two-story house, designed to lug rock, drove over the smaller vehicle, flattening it. Benavidez, 52, was caught in one of the haul truck’s blind spots and crushed to death.

The mining industry has known for decades about these blind spots and the role they played in dozens of deaths. All the while, the U.S. Department of Labor’s Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) has pushed companies to install readily available and relatively cheap safety features that, it says, could save lives.

Mining companies and trade groups have responded with strong opposition.

A Center for Public Integrity review of MSHA investigative reports, police files and court documents reveals that weak oversight has mixed with mistakes at mines to deadly effect, as the industry and its regulators bicker over proposed rules. Various types of heavy machinery have directly or indirectly been involved in nearly 500 deaths, dozens of them caused by blind spots, at underground and surface mines since 2000, according to MSHA data.

A recent analysis by the agency found that 23 deaths could have been avoided in surface mines alone between 2003 and 2018 if heavy machinery were equipped with safety measures such as backup cameras, proximity sensors or other collision-warning systems.

Benavidez suffered one of those avoidable deaths when a haul truck driver, even after following the mine’s safety protocols, never saw Benavidez’s Chevrolet pickup and drove over it. A mechanic in the seat next to Benavidez was extricated from the vehicle, but with serious injuries.

“Think about having a million blind spots all around you,” Benavidez’s 30-year-old daughter, Amanda, said. “That’s what it’s like to be in one of those. You don’t know what’s right under you.

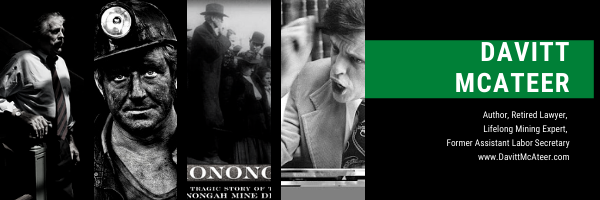

“These large haulage trucks cost a fortune, but inexpensive camera systems which are currently available, are not required by MSHA,” Davitt McAteer, the head of MSHA during the Clinton administration, wrote in a statement accompanying testimony before Congress in 2007. “In the late 90s, I initiated a voluntary program to encourage operators to install them, and sadly that program has languished in the last several years.”

INDUSTRY OPPOSITION

McAteer blames the industry, particularly the politically powerful National Mining Association, for the lack of progress on blind spot deaths. “Rules can be stalled now by virtue of anything,” he said. “The association’s bread and butter is to stall. That is their whole reason for being.”

The association came out against proposed rules in 2011 and 2015 requiring proximity-detection systems on underground continuous miners and mine vehicles.

In recent, written comments, the trade group acknowledged that such systems could increase safety in surface mines and that some mining companies were using them. But it said more research is needed, and, in general, “rapid introduction of unproven technology can pose unforeseen safety risks.”

In a statement to the Center for Public Integrity, the association said it did not track the extent to which its members employed these safety features, although “safety is the top concern for mining companies.”

State mining associations also wield considerable influence. The Nevada Mining Association, for example, fought the same rules proposing the use of proximity-detection systems, saying the technology wasn’t advanced enough.

“Safety is the highest priority for the Nevada Mining Association and its members,” association president Dana Bennett said in a statement. But she said that retrofitting equipment is difficult because “third-party aftermarket devices have often been found to be complex and have unintended consequences that pose potential risks.”

www.DavittMcAteer.com Davitt McAteer & Associates